- News articles

First published in the Financial Review on 28 January 2021.

Rejoicing at the indexation of the transfer balance cap from July 1 because you’ll get more in tax-free pension phase? How it will work is likely to be frustrating.

Since July 1, 2016, the complexities in administering superannuation accounts, particularly SMSFs, has significantly increased. There are numerous thresholds, caps, indexation methods and limits that require constant monitoring and reporting.

This is not only difficult for trustees and members, but also their advisers, who in many cases are unable to access the necessary data in an accurate and timely fashion.

The different total superannuation balances (TSBs), individual transfer balance caps (TBCs) and imminent proportional indexation, the lack of SMSF adviser access to the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) portal and the intended removal of annual TBC reporting obligations all combine to create excessive complexity.

From July 1, this is only going to get more complicated.

Superannuation members have their own personal TBC that determines the amount they can transfer into retirement-phase income streams. Initially a personal cap will equal the general TBC in the year they first have a retirement phase income stream count against their transfer balance account. Currently, this is $1.6 million.

Due to the December consumer price index reading, the current general transfer balance cap will be indexed from $1.6 million to $1.7 million. So far, not so bad. However, when proportional indexation is considered, the situation changes.

Over time, a client’s personal cap may differ from the general TBC because of proportional indexation. Under proportional indexation, the unused portion of the client’s personal cap (based on the highest percentage usage of their TBC) will be indexed in line with the indexation of the general transfer balance cap. This is an overly complex situation that will result in many superannuation members having a personal TBC different from the general TBC.

Those who haven’t used any of their cap will have a TBC of $1.7 million; individuals who have used a portion of their cap (based on their highest percentage usage) will fall somewhere between $1.6 million and $1.7 million; and individuals who have used all of their cap will remain at the original TBC of $1.6 million.

Because of the complex proportional indexation method, it is anticipated there will be a lack of understanding by professionals and individuals on how correctly to calculate a member’s personal TBC to avoid triggering an excess.

We will have a system where many individuals will need to calculate their own TBC that will be different to everyone else’s personal TBC. Not understanding and calculating your own balance accurately could leave trustees liable for excess transfers to the retirement phase.

Case Study

Leanne started a retirement phase income stream on October 1, 2017 with a value of $812,000. On May 13, 2019, she commuted $200,000 from her pension and her transfer balance account was debited by $200,000. Although the balance of her transfer balance account when indexation occurs is $612,000, the highest-ever balance of her transfer balance account is $812,000.

Leanne’s unused cap percentage is 49.25 per cent of $1.6 million. Her personal TBC will be indexed by 49.25 per cent of $100,000. Leanne’s personal TBC after indexation is $1,649,250.

Leanne must be aware that if she chooses to increase her retirement phase income streams, she must calculate her personal TBC based on her specific proportional indexation percentage and increase it to a maximum of $1,649,250 and not to $1,700,000. Leanne must also be aware that her personal TBC will be different to everyone else’s. It is likely she will need advice to calculate it accurately.

Other Fixes

The calculation and monitoring of indexation and the personal TBC are complex and introduce another element of confusion.

One solution is to remove the need for proportional indexation. This would be implemented by “locking in” an individual’s TBC to the general TBC when they first started a retirement phase income stream. For example, any individual who has started a pension currently would be subject to a $1.6 million TBC.

Although this option may cause some minor inequities, these are acceptable to avoid the cost and confusion that proportional indexation would cause.

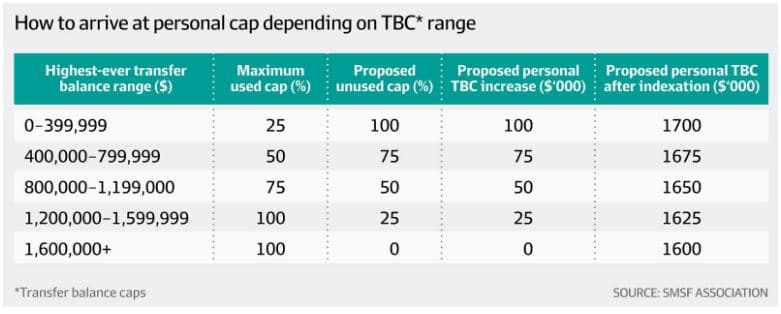

Another proposal is to reduce the number of bands (currently 0 per cent to 100 per cent) of proportional indexation to just four (illustrated in the table).

In this example, the number of bands an individual’s personal TBC may fall into has been simplified. Individuals will know their highest TBC and know they will only fall into one of the four bands, hopefully making it easier for trustees to navigate their TBC calculations.

In the absence of providing everyone an additional $100,000 to their TBC (which goes against the intent of the TBC,)or simplifying the formula in some way, the only other step is to ensure that individuals and their advisers have access to timely and accurate data from the ATO and can act on it.

Unfortunately, this is not the case. Accountants can obtain information from the ATO portal but cannot provide advice on contributing to pensions and financial advisers are unable to obtain that information but are the advisers authorised to provide advice. This jeopardises the quality and efficiency of advice that is being provided to members.

The Retirement Income Review report found that the system is complex. The aim should be to keep complexity to a minimum – addressing proportional indexation would be a good start.

Opinion piece written by

John Maroney, CEO,

SMSF Association